|

William Gilbert, Arthur Sullivan and Richard D’Oyly Carte met at Sullivan’s

residence on Christmas morning, 1887. The occasion was not an exchange of

gifts, in the usual sense, but everyone received a present nonetheless. For Gilbert

had the outline of a story for a new opera, which he reported to his two

colleagues. Sullivan, in his diary, wrote: "Gilbert read plot of new piece (Tower

of London); immensely pleased with it. Pretty story, no topsy-turvydom, very

human and funny also."

William Gilbert, Arthur Sullivan and Richard D’Oyly Carte met at Sullivan’s

residence on Christmas morning, 1887. The occasion was not an exchange of

gifts, in the usual sense, but everyone received a present nonetheless. For Gilbert

had the outline of a story for a new opera, which he reported to his two

colleagues. Sullivan, in his diary, wrote: "Gilbert read plot of new piece (Tower

of London); immensely pleased with it. Pretty story, no topsy-turvydom, very

human and funny also."

The fact that Sullivan liked the new idea was music to the ears of both Gilbert

and Carte. Gilbert had been vainly trying to interest Sullivan in various versions

of his "lozenge plot," in which the characters, by swallowing a pill, became who

they were pretending to be. Sullivan, in a September diary entry, rejected the

tired gimmick as "a puppet show." It is impossible to feel any sympathy with

any single person. He was relieved, therefore, when Gilbert finally admitted

defeat and offered a much more human story.

Carte was probably even more relieved to find the partners at last in agreement.

Ruddigore had closed after a disappointing, for G. and S., run of 288 performances, and a new show was needed for the Savoy Theatre. Revivals of H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado were to keep the lights on, but the public had begun to suspect that Carte’s gold mine was running out of ore. (Can you imagine

today a theatre devoted exclusively to performances by one company and written by only one composer/librettist team?)

Gilbert claimed that the idea for the show had come to him when he was waiting at the train platform in Uxbridge and spotted an advertisement for the Tower Furnishing Company, illustrated with a scene of the Tower of London, or a Beefeater, depending on whose version you read. The title was originally (or not very originally, as the case may be) The Tower of London, then The Tower Warder. Gilbert felt he wanted something stronger, but his

suggestion of The Beefeaters met with a cool response from Sullivan, perhaps thinking of the public’s reaction to the original spelling of its predecessor, Ruddygore. One expert has noted that the final version, The Yeomen of the Guard, is not, strictly speaking, accurate, since the Yeomen, although they wear a similar uniform to the Tower Warders’, are actually the personal bodyguard of the monarch, and not connected with the Tower at all.

While Gilbert wandered the Tower grounds, soaking up Tudor atmosphere for his writing, Sullivan was off in Monte Carlo and Algiers, recuperating from one of his many bouts of illness. Suddenly a new crisis. A rival musical, Dorothy, with music by Alfred Cellier, who often assisted with the G. and S. performances, was achieving a run that was to outpace even that of The Mikado. Sullivan seems to have decided that it was time for him to leave light opera to someone else. Carte also seems to have been trying to move the company to a new and different

level. Urgent letters back and forth (Gilbert: "We are world-known and as much an institution as Westminster Abbey.") and the waters were calmed again.

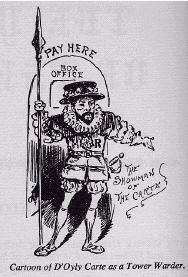

Gilbert always felt the most isolated of the triumvirate. Sullivan’s closer connection to D’Oyly Carte was underlined by an otherwise happy event on April 12, 1888. D’Oyly Carte married his long-time secretary, Helen Lenoir, and Sullivan was the best man. The Cartes’ new home would feature an elevator, foreshadowing the luxury of Carte’s next venture, the Savoy Hotel. And the impressario was already dreaming of the Royal English Opera House, for serious musical drama, where Sullivan could respond to the urgings of no less a personage than Queen Victoria that he write a grand opera. ("You would do it so well.") The causes for friction were never far below the surface.

Nevertheless, Gilbert took great pains to ease Sullivan’s efforts, sometimes writing two or three versions of a lyric, to allow the composer more choice. Sullivan is even on record to admitting that Gilbert rescued him when he was stuck on a rhythmically correct tune for "I have a song to sing-O!" by humming the sea shanty that he had in mind when penning the lyrics (a Cornish song somewhat like "Green grow the rushes O"). And so, despite lurching from crisis to crisis, the team worked their old magic, truly combining talents on what was to become the signature song of a dramatically different collaboration.

|